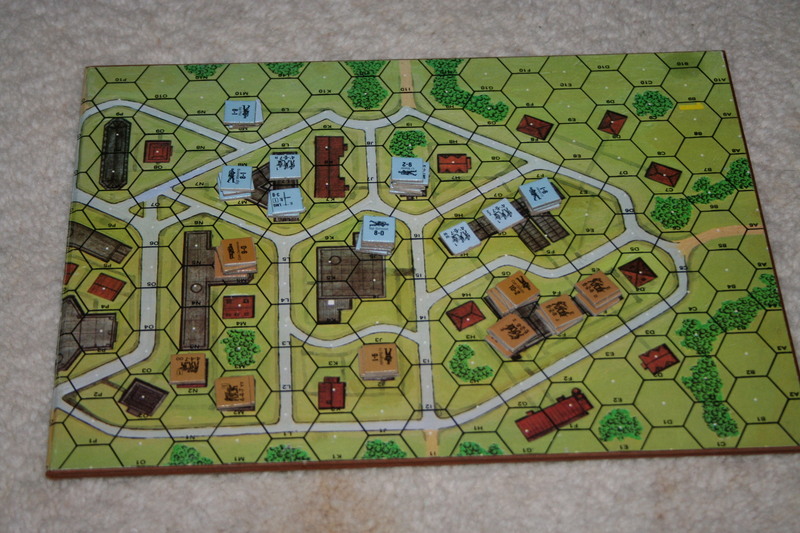

ASL Boards on Google 3D

Someone’s been using Google 3D to do some cool basic renderings of the ASL geomorphic map boards.

Update 2/25: Here’s another.

Permalink Comments off

Someone’s been using Google 3D to do some cool basic renderings of the ASL geomorphic map boards.

Update 2/25: Here’s another.

Permalink Comments off

Here’s a nicely laid out sample game of Bonaparte at Marengo, which I’ve previously written about. BaM is not your typical hex and counter wargame—for one thing it uses neither hexes nor counters nor dice—but it’s well worth a look from anyone interested in just how innovative and elegant wargame mechanics can get. There’s no analytic commentary, just turn-by-turn illustrations of the moves, so the casual reader won’t take away much about actual strategy and decision-making, but the rules themselves are also available for free download and will illuminate the sample game.

See also designer Bowen Simmons’ essay, “Chance and Wargames.” Rumor has it we should see his next project as soon as the end of this month, Napoleon’s Triumph, an expansion and revision of the BaM system to cover the battle of Austerlitz.

Austerlitz, incidentally, is a notoriously difficult battle to game, which gives me an idea for another post . . .

So I mentioned I did some pike pushing last weekend.

The game in question is entitled This Accursed Civil War, designed by Ben Hull and published by GMT Games. The box contains maps and counters for playing five battles from the English Civil War. This Accursed Civil War is itself part of a series of games entitled the Musket and Pike Battles Series. Other games in the series cover battles from the 30 Years War on the continent, a conflict characterized by the technological transition from armies with long, pointy sticks to armies with gunpowder weapons. Hence the title, Musket and Pike.

The series concept is worth a note or two. As I’ve previously suggested, learning rules is probably the single biggest impediment to the actual play of board wargames. With series games, however, you have a common rules set that is applicable to multiple titles in the series. Having learned the Musket and Pike rules and owning all four games in the series, there are about 20 different battles I can play right out of the box. Some readers will recognize this as an expansion of the old SPI concept of the quadrigame, which also used a common rules set to play four different games all packaged together. Relying on a single rules set to cover diverse situations can sometimes straightjacket a designer, but the format also allows for a page or two of game-specific rules that apply only to the battle at hand.

The idea of gaming a “battle” is also worth a mention. As I’ve also noted elsewhere, wargames come in several different scales. Rather than gaming a particular battle, I could have opted to play a game that would cover the entire English Civil War. The battle game is the mainstay of the hobby, however; sometimes referred to as “grand tactical” level games, the appeal is that you have a well circumscribed historical event and the player has a clear role to occupy, namely that of the army commander.

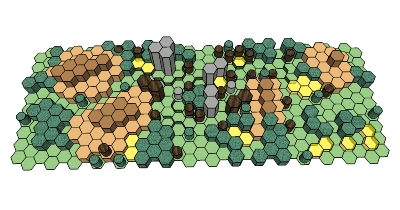

The battle we played was Marston Moor, the largest and bloodiest fight of the English Civil War, featuring a mixed force of Parliamentarians and their Scots allies against a Royalist army under Prince Rupert outside of York. See Wikipedia for more of the history. Here’s how the game looks set up; the Royalists are in blue, the Parliamenterians in red, and the Scots in green:

And here’s a close up of the Parliamentarian cavalry wing under the command of one Oliver Cromwell:

Because the armies of the day needed open ground to deploy effectively, most battlefields in this period were anonymous open terrain. There were no inherent geographical objectives, nor were the battles themselves subtle affairs; the objective was typically to drive the enemy from the field and one did this by killing. Here the only terrain feature of note is the hedge which affords a portion of the Royalist line some scant cover. One wins the game by inflicting casualties on the enemy.

What’s subtle is the actual game play, or as a tactician might put it, “battle management.” Here’s also where the current state of the art in game design becomes visible. Were this an old style SPI wargame, such as the once very popular 30 Years War Quad, each player would be free to move all of his units every turn in whatever manner he wished, subject only to the limitations of terrain and the presence of the enemy. Units would engage in combat until eliminated, and units would perform at peek effectiveness until eliminated. The player enjoyed an omniscient perspective on the proceedings and was free to act on it.

Here, however, things work differently. As was the case historically, these cardboard armies are divided into “wings,” left, center, and right. In this era one typically had a heavy infantry center, and cavalry on either wing. The game system mandates that each wing always be in one of four Orders States: Charge, Make Ready, Receive Charge, and Rally. Each Orders State comes with inherent constraints that dictate a unit’s offensive and defensive capabilities. Changing from one Orders State to another is the job of the Wing Commanders, who are represented by counters rated for their historical performance. Thus Cromwell will prove much more adept at changing orders for his wing than another, more mediocre commander on the field. (The success or failure of the actual orders change is resolved by a die roll, modified for various factors.) Note that the player’s authority is here being dispersed among his cardboard representatives; as Army Commander, you might spot a perfect opportunity for your cavalry wing to charge, but if the Wing Commander can’t convert orders from Make Ready the rules will forbid engagement with the enemy. What we have then, is fog of war via procedural abstraction—the game system willfully imposes friction on a player’s ability to operate in an effort to model a variety of battlefield effects that would impinge on the abilities of a real commander, everything from a bumbling performance by subordinate to literally being unable to see through the thick powder smoke.

Most armchair generals will drive their cardboard troops relentlessly; this often produces a-historical results, because it allows an army to fight to the last man. Thus the critique that a game system is too bloody is one of the most common in wargaming. Far from being a hawkish virtue, a “bloody” system means that the game produces too many casualties, typically because the armchair generals are using their troops in a way that no historical commander ever could or would. At Marston Moor there were about 4000 casualties in some two hours of fighting, extreme by the standards of the day. A good recreation of the battle should produce about the same loss rates. A good game system thus reflects the way a unit gradually looses effectiveness over the course of an engagement. Musket and Pike actually tracks a unit’s current effectiveness on three separate vectors: formation, morale, and casualties. Mechanically this is done by placing marker counters on top of or underneath the individual unit.

It is extremely rare in Musket and Pike for a unit to dwindle away to nothing through actual casualties received. Typically, what happens is that the unit’s morale—an abstract representation of its will to fight—degrades until it eventually “breaks” and retreats (“routs”) from the combat, regardless of the wishes of the player. Likewise, given that the armies of the day required tight, disciplined formations to fight effectively, the game system tracks the deterioration of ranks through movement over difficult terrain, contact with the enemy, and other debilitating effects. Formation and to some extent unit morale, though never actual casualties, can be restored through Rally actions, but this involves pulling units out of the fight and giving them time to recover. Hence battle management, that is managing your martial resources by feeding fresh troops into the fray in order to maintain pressure on the enemy. Musket and Pike battles are typically won when one player is able to break the other’s battle management cycle, that is inflict losses faster than his opponent is able to recover from them, eventually causing their position to collapse, at which point the army will rout and cede the field.

In the actual game, I had the Parliamentarian allies. After an ineffectual artillery barrage my heavy infantry center lurched forward, a couple of formations foundering due to the enemy guns, but if there’s one thing the Roundheads have in this scenario it’s heavy infantry. The real action, though was over on my left, where I activated Cromwell’s cavalry wing. Despite managing to get Cromwell himself killed early on I pretty much pulverized my opponent’s right wing and was able to turn the whole flank. The constraints of the orders system meant he couldn’t get his guys out of Receive Charge to redeploy and meet the threat. The Allies achieved a decisive victory, dear old Cromwell fertilizing the daisies notwithstanding.

ZOI is now Zotero-enabled, via a cool plug-in that adds COinS metadata to each entry. (If you don’t know what Zotero is, go find out.)

Permalink Comments off

Was out at my favorite local game store today, the Game Parlor in Chantilly, Virginia, where I gamed Marsten Moor, a musket and pike battle from the English Civil War (more on that in a separate post).

Despite a thriving scene with throngs of players having at board-, figure-, and role-playing games of all stripes, brick and mortar game stores get by these days by the skin of their teeth; so I always try to spend a little money after spending a part of my day under their roof. Today I restrained myself and rather than a game took home a copy of H. G. Well’s 1911 book Floor Games.

Now Wells is best known in ludology circles for a book he wrote a couple of years later, Little Wars, “for boys from twelve years of age to one hundred and fifty and for that more intelligent sort of girls who like boys’ games and books,” as the text is most obnoxiously subtitled, which introduces simple rules for playing games with toy soldiers. Floor Games is a gentler sort of book, though it’s not above references to “negroid savages” and other charming trappings of Empire.

Here’s how it begins, seeming to anticipate the idea of the magic circle several decades before Huizinga set it down in Homo Ludens:

The jolliest indoor games for boys and girls demand a floor, and the home which has no floor upon which games may be played falls so far short of happiness. It must be a floor covered with linoleum or cork carpet, so that toy soldiers and such-like will stand up upon it, and of a colour and surface that will take and show chalk marks; the common green-coloured cork carpet without a pattern is the best of all. It must be no highway to other rooms, and well it and airy. Occasionally , alas! it must be scrubbed—and then a truce to Floor Games! Upon such a floor may be made an infinitude of imaginative games . . . (3-4)

The chapters that follow sketch out a series of games with titles like “The Game of the Wonderful Islands” (not so wonderful, perhaps, for the aforementioned indigenous populations, consigned by Wells to chasing wild goats around the hills or accosting the encroaching imperialists). Indeed, the unabashed colonialist trappings of those Edwardian spaces are unfortunately reminiscent of the premise of the highly successful modern Euro game Puerto Rico (Rio Grande), in which players are cast in roles that essentially amount to slave traders (excuse me, “plantation owners”). What all of the scenarios have in common though is an emphasis on improvisational play, emergent narrative, and building physical play spaces out of common house-hold materials (here, as in Little Wars, Wells exhibits a general disdain for commercial toy manufacturers).

As the introduction also notes, in several places he comes very close to articulating the principles of what we would today recognize as a role-playing game. It’s worth a look, at least for the historically-minded ludologist. More on my pike pushing anon.

Permalink Comments off

So the rubble was still settling in the aftermath of some hard-fought actions in the streets of Stalingrad when my adolescent self, lo these many years ago, turned to the fine print at the back of the original Squad Leader rules booklet and read the following in the Designer’s Notes: “Any knowledgeable wargamer will see at a glance that the terrain of SQUAD LEADER has been abstracted to better capture the ‘feel’ of infantry combat. . . . The Dzerhezinsky Tractor Works alone was an immense complex that could not be accurately portrayed by 8 of our city mapboards! Indeed the Germans didn’t succeed in breaking into the Tractor Works until . . . 200! German tanks had assaulted the outer defenses.†Though I had been playing hex and counter wargames for several years and probably instinctively understood that realism was a problematic word applied to dice and cardboard and CRTs, this was the first time I had seen the concept of “abstraction†so unabashedly articulated. Suddenly my team of crack assault engineers storming into the Tractor Works under cover of smoke and HMG fire didn’t seem like such an achievement—the “factory†was only a piddling little cluster of hexes. I played SL and the rest of the series happily for many years afterwards, but that discrepancy always nagged at me. Maybe, I thought, I could get 8 or 10 more city boards and 200 tank counters and make it right?

Of course Red Barricades, the first module in the historical ASL (HASL) series proceeded to do exactly that not too many years later. Historical ASL—even the name is telling—exposes some interesting tensions in the game system. Most ASL scenarios are played on generic or so-called geomorphic map boards, whose layouts depict a “typical†village, forest, piece of a city, etc. Despite the fact that the historical basis of the geomorphic scenarios was usually carefully established, the geomorphic map boards themselves—literally the foundation of play—were always a conspicuous abstraction. HASL was, in effect, the game system’s clearest acknowledgement of this phenomenon, substituting depictions of actual terrain (the Red Barricades maps were derived from aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by the Luftwaffle).

Urban terrain depicted with an ASL geomorphic board (left), Red Barricades (center), and actual aerial photograph of Stalingrad during the fighting.

One of the more brutal and bitter fights that occurred during the combat in Stalingrad in late 1942 concerned a Soviet stronghold that had come to be known as “the commissar’s house.†The ASL system features two scenarios that recreate this particular action, one using the geomorphic boards and one played on the Red Barricades map. Both are ultimately abstractions—the “historical†map includes stone walls whose 60-degree angles follow the outlines of the hex-grid, for example. But some interesting observations can still follow. In particular, I’m interested in whether wargame scenario design can be fruitfully mated with an area of analytical philosophy known as possible worlds theory. Possible worlds theory has in turn spawned applications in domains like narratology. Surely it is relevant to the design of interactive simulations, electronic or otherwise. In particular, I’m interested in thinking about possible worlds theory in relation to immersion or suspension of disbelief. When we play a geomorphic ASL scenario called “Counterstroke at Stonne,†we know that board 3 isn’t meant to be the small French village of Stonne, not exactly . . . but it could have been, and at a certain point we’re willing to suspend disbelief. Using a desert board, by contrast, would certainly be enough to break the illusion as would a major geographical feature like a river. But what about the chateau that’s depicted on one of the geomorphic boards used in the scenario, which, the story goes, is there because the designer read about a “chateau d’ eauâ€â€”a water tower. Whoops. A glitch, but one that has no real impact on the integrity of the scenario—after all, there could have been a chateau just outside the rural French village of Stonne, right? Had the false chateau appeared in a treatment of the battle based on actually terrain (like Red Barricades did for Stalingrad) it would have been regarded as a far more serious matter. But given that all such maps are still ultimately abstractions, how then can we account for the difference? Can possible worlds theory help here?

A correspondent sends word of the following, apparently just published:

ACHTUNG SCHWEINEHUND is about men and war. Not real war but war as it has filtered down to us through toys, comics, games and movies. It is about blokes who spend their leisure time dressing as Vikings, applying transfers to 1/32nd scale plastic models of armoured personnel carriers or re-fighting El Alamein with stacks of cardboard counters. Take a journey into a darkened backroom where HG Wells, a secret service assassin and the Bronte sisters rub shoulders with men called Dave who can identify 376 different WW2 camouflage patterns; a world where the apparent polar extremes of masculinity – brutal violence and the obsessive desire to memorise code numbers and create acronyms – co- exist peacefully in an atmosphere rich with the hallucinogenic fumes of polystyrene cement, cellulose thinners and bright orange corn-based snack foods. ACHTUNG SCHWEINEHUND is a book for any man who can’t smell enamel paint without thinking of the Airfix 8th Army set, who remembers watching Rat Patrol, reading Battler Briton and playing Escape From Colditz. Or for any woman who has ever asked herself why the first thing most boys make from Lego is a sub-machine gun.Â

I don’t see it on Amazon yet, but a UK outfit seems to have it in stock.

I will be out in Berkeley next week for this day-long symposium on New Media and Social Memory.

Unfortunately, however, I will still not get a chance to meet Stanford’s Henry Lowood, who despite being a games scholar, digital preservationist, fellow Kittler reader, and fellow wargamer I’ve yet to encounter f2f. (Henry, as it turns out, will be busy hosting John Unsworth, with whom I wrote my dissertation. Sigh.)

Comprehensive list of board wargames published in 2006, compiled on behalf of the International Gamers Award Historical Simulations Committee. Over 100 items on the list.

Remember the scene in The Matrix where they’re slotting cartridges into Neo’s head and he sits up and says “I know Kung Fu”? That’s every wargamer’s dream, except they’d want to sit up and say “I know ASL.” You get a new game, you pull off the shrinkwrapping, you unfold the map and fondle the components, but then there are the rules, oh man, the rules. Wargamers spend a lot of time with rules. Rule books often run 32 or 48 pages; anything 16 pages or less is considered “short.” Not surprisingly, wargamers have a different relationship to rules than most gamers. Reading rules it not “fun,” not exactly, but it’s part of the hobby and not without intrinsic interest and even art.

Games often have learning scenarios or programmed instruction sequences so players can gradually absorb a complex rules set, playing the game and layering on a new rules section every time. Some gamers set up a game and learn by pushing the pieces around, others like to give the rules a complete read through first. (There’s an ethnographic gold mine here for anyone interested in procedural learning.) Many games borrow and re-use similar concepts, and part of the interest of the hobby is viewing the rules as a window onto how designers are thinking about their subject and where they’re choosing to innovate. Yet many rule sets are ambiguous, poorly written, or otherwise open to interpretation and variants. Given their scope and complexity, wargame rules almost invariably have errata. In the old days, you would get the errata by sending a SASE to the publisher or maybe through one of the hobby’s house organs or zines if you had a subscription or were lucky enough to catch the right issue. Nowadays, of course, errata is available over the internet, and this distribution platform has changed the way rules are developed. Game companies have evolved the practice of “living rules,” where the ability to use the Web to electronically distribute rules means that a rules set is not necessarily fixed and inviolate once a game is published. Some gamers consider this a mixed blessing, partly because the rules can change under your feet, but also because the availability of living rules can sometimes become a crutch for shoddy playtesting.

Living rules turns out to be any interesting bit of phrasing, given the conventional wisdom that game rules are absolute and inviolate. Certainly this holds true for traditional games like Chess or Scrabble, but even contemporary Euro games tend to have very stable rules sets. One notable exception concerns the scoring of farmers in the popular tile laying game Carcassone, but even there you have variants rather than a living, evolving rules set. Wargames, by contrast, offer a game genre where rules sets are often malleable, based on player feedback, the deisnger’s changing intentions, new historical research, or all of these. Rules are therefore social texts, at least sometimes determined by the experience of a player community. (I would hasten to distinguish this from games played as part of folk traditions, where rules and variants are passed down orally.)

In the comments below, E Holmes says:

games are not static objects but are living, evolving structures that begin and end with human experience and involvement

With this I agree absolutely, but I have to depart from him on the next point:

Games are a human experience and reflect human experience; they do not operate on formal laws existing in any external ‘reality’.

In fact I think what’s unique about games is precisely that they operate on formal laws that arbitrarily impinge on our own reality. This of course is the well known concept of the “magic circle,” after Huizinga. Wargming underscores the extent to which the magic circle is a social construct, the product of a particular community of experts and enthusiasts. But to deny the formal ontology of games seems to me to deny the possibility of game play itself as anything other the unstructured make-believe play of a child. Or Calvinball. Agreeing that games (and their rules) are living, evolving artifacts seems to me to restore a useful social and material dimension to game studies, but it does not follow that we have to deny the formal ontology of game play.