Open Thread and Guestbook

First time here? Leave and comment and let me know what you think of the blog so far. What kind of topics would you like to see discussed here? If you are a ludologist, what do you know about wargames?

First time here? Leave and comment and let me know what you think of the blog so far. What kind of topics would you like to see discussed here? If you are a ludologist, what do you know about wargames?

Jesper Juul, in Half-Real (MIT 2005) writes about rules: “Game rules are designed to be easy to learn, to work without requiring any ingenuity from the players, but they also provide challenges that require ingenuity to overcome” (55). He continues:

Rules are designed to be above discussion in the sense that a specific rule should be sufficiently clear so that players can agree about how to use it. Rules describe what players can and cannot do, and what should happen in response to player actions. Rules should be implementable without any ingenuity. (55-6)

According to Juul, “Easy to learn but difficult to master” is the paradox at the heart of good game rules. But games with procedurally complex rules are not necessarily flawed or bad games. Advanced Squad Leader (ASL), originally published by the Avalon Hill Game Company, is undoubtedly the most procedurally complex wargame ever designed, and quite likely by extension the most procedurally complex boardgame ever designed. It is not easy to learn, nor master. The game (more properly, game system, you acquire it as a series of modules) focuses on Word War II small unit combat, with counters representing infantry squads and individual leaders, vehicles, and heavy weapons. Here is not the place to go into detail about ASL itself, which in theory allows a player to recreate any small unit action from any theater or phase of the war (see the Wikipedia entry linked above). What I want to focus on is the role of player error in the play of the game. Given the size, scope, and complexity of ASL’s rules—its procedures and their interactions—human error in the application of the rules is inevitable. This situation is anticipated in the rules manual itself (some 200 pages long), with the second rules case of the game stating the following:

A.2 ERRORS: All results stand once play has progressed past the point of commission. In other words, if an error is discovered after play has passed that point, the game cannot be backed up to correct the error, even if such an error is in violation of a rule. For example, assume an attack is resolved without application of a proper DRM [dice roll modifier], and a subsequent attack is resolved, or another unit moved, or play proceeds to another phase before a player remembers he was entitled to a DRM in the previous attack, thus changing the result. His failure to apply that DRM at the time of commission has cost him his right to claim that DRM. Or perhaps a player moves a unit before remembering that he wanted other units to attempt rally in the RPh or fire or entrench in the PFPh. Once the phase for execution of a particular action has passed, the player has lost any claim to that capability.

Thus the game builds the provision for error into its own formal system, so that error is accommodated within the formal structure of game play. The issue with ASL is not that the rules are badly written—the rules manual (pictured below) is for the most part a model of technical clarity—but that the number of rules, and their interactions and permutations is so vast that it is unreasonable to think human players, even experts, will always implement all of them correctly. (Early examples of play published in Avalon Hill’s own house magazine, The General, contained flagrant errors.) On the one hand then, a game of ASL’s formal scope and complexity represents a kind of limit case for Juul’s discussion of rules. (The number of interactions is so complex that ASL players has evolved an axion, COWTRA, “concentrate on what the rules allow.”) Yet ASL also provokes other kinds of questions, including what kind of pleasure one gains from playing such a procedure-heavy game.

An ASL game scenario is a kind of world building. In Juul’s terms, it is both incomplete and (occasionally) incoherent. The game system is capable not only of accommodating movement and firing, but a vast array of other actions. A building struck by an artillery shell may “rubble,” in turn collapsing other buildings around it. Underbrush may be set on fire. Squads may generate heroes, who can become wounded, but nonetheless survive to scrounge an abandoned machine gun which might then malfunction only to be repaired and then lost when the wounded hero is captured (he may then escape). A tank can throw a tread as it crashes through a wall, rotating its turret to fire at a target glimpsed for a moment through a narrow village street. These extraordinary permutations of rules interactions generate what players routinely refer to as “narrative.” (ASL is often described by its fans as representing not real world small unit combat, but World War II as it was refought in Hollywood film.)

Here is some of what ASL has to teach us about complex game rules:

I will be writing more about ASL in future posts, including its capacity for “narrative” and possible worlds theory.

Why should the contemporary academic ludologist, especially one interested in video games, bother with board wargames? I would argue for at least the following reasons:

Permalink Comments off

Some readers will not be familiar with the genre of board wargaming. Below is a large-scale example of the type, a game entitled Europa, actually a composite of a series of games originally published in the 1980s, laid out for play at Origins 2006. It depicts all of WWII in Europe, the Mid-East, and the Soviet Union. Each hex represents 16 miles, each game turn represents two weeks, and units (the individual counter tokens) are typically divisions.

Photo credit: Michael Dye. Used with permission.

Things to notice:

A final point. Hovering over the maps, the players occupy an implicit position in relation to the game world. They enjoy a kind of omniscience that would be the envy of any historical commander, their perspectives perhaps only beginning to be equaled by today’s real-time intelligence with the aid of GPS, battlefield LANs, and 21st century command and control systems. The player’s relationship to the game is (to me) one of the most interesting aspects of board wargames, and I intend to explore it at length here in Zone of Influence. For now, suffice to say that “fog of war,” chaos, and friction are de facto qualities of any military situation, and they have been expressed, with varying degrees of verisimilitude, in existing game mechanisms.

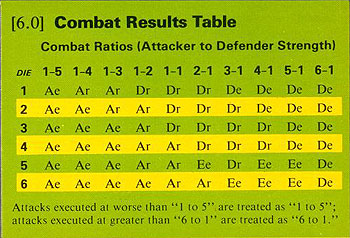

Napoleon at Waterloo, a classic game originally published by SPI in 1979 (and the source of the CRT above), is available in its entirety for inspection and download here.

Permalink Comments off

A Zone of Influence (ZOI) is a lesser-used cousin of a common hex and counter board wargaming mechanic known as a Zone of Control. Typically a unit in another’s ZOI has its movement hindered or impaired, whereas the stronger ZOC might prohibit movement altogether, and/or mandate combat. This is a classic ZOI or ZOC diagram:

This blog is a zone or space where I think I might be able to exert some influence on game studies. Hopefully people will slow down and take time to read and engage in conversation, if not combat. The blog is also a space where I can combine my interest in boardgames (especially board wargames) as a hobbyist and enthusiast with my academic interests in games, simulation, and technologies of representation.

I intend to try my best to find some interesting and original things to say about board wargames, which were a commercial game publishing genre of considerable popularity and market share throughout the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and which continue to mark the material and ergonomic extremes of board games as physical and formal systems. (Board wargames are notorious for the length and complexity of their rulebooks, with 32 pages or more not uncommon; a typical game will have dozens or hundreds of unit counters [tokens] in play at once, maps covering a playing area of up to a dozen square feet, and can take multiple gaming sessions, each of many hours, to finish to completion.) Board wargames are also of interest to me as cardboard computers; they are instruments for modeling, prediction, and prognostication, but by their nature they are open source with the algorithms laid bare in numerically expressed outcomes on charts and tables. The only “black box” is the designer’s intentions. Frequently a collector will have multiple games on the same subject, the idea being to examine how well each models the relevant history. (As Greg Costikyan has pointed out, the term “game designer” was first used in conjunction with board wargames.)

Abstract games with martial themes date to antiquity, so in the same way that Jesper Juul asks why play games with computers rather than devices like microwave ovens, one might also ask why play games about war as opposed to games about cooking. I’d much rather be in a kitchen than in a battle, but warfare and gameplay have a long, deep, intertwined history with one another, much as the world’s militaries have a deep and intertwined history with computers and computing.

While I think ludology can learn things by paying attention to board wargames, I also want to look at the games on their own terms—critically—for their mechanisms and material affordances, in ways it’s sometimes hard to do on the various fan sites that I frequent. But I hope some friends from those sites will find their way here, and that there can be some productive dialogue between hobbyists and academics. Finally, board wargames will by no means be the only subject I take up here; Zone of Influence will also be a platform for discussing many other aspects of game studies and new media.

A quick word about politics: given that wargames deal with military history and military themes, one might assume they are played by milititary fetishists and hawkish militarists, a particularly noxious constituency given the current world situation. My own politics are liberal/progressive, as are those of a number of people I’ve encountered in the hobby. The two largest constituencies in board wargames seem to be active duty or retired military personnel, and computer/IT workers. The attraction of the hobby to the former group is obvious but the latter is not surprising either, for reasons I will explore. There is also a sizeable contingent of educators in the hobby (Jim Dunnigan, patriarch of the venerable SPI, has pronounced wargaming the hobby for the over-educated, and Avalon Hill often traded on this image in their ad copy). Anyway, please, no assumptions about my personal politics, or that I harbor any illusions about the reality of warfare, emphatically not a game for far too many in this world.

Permalink Comments off