Your Author in Action

With the DC Conscripts last weekend (left).

Permalink Comments off

Someone’s been using Google 3D to do some cool basic renderings of the ASL geomorphic map boards.

Update 2/25: Here’s another.

Permalink Comments off

So the rubble was still settling in the aftermath of some hard-fought actions in the streets of Stalingrad when my adolescent self, lo these many years ago, turned to the fine print at the back of the original Squad Leader rules booklet and read the following in the Designer’s Notes: “Any knowledgeable wargamer will see at a glance that the terrain of SQUAD LEADER has been abstracted to better capture the ‘feel’ of infantry combat. . . . The Dzerhezinsky Tractor Works alone was an immense complex that could not be accurately portrayed by 8 of our city mapboards! Indeed the Germans didn’t succeed in breaking into the Tractor Works until . . . 200! German tanks had assaulted the outer defenses.†Though I had been playing hex and counter wargames for several years and probably instinctively understood that realism was a problematic word applied to dice and cardboard and CRTs, this was the first time I had seen the concept of “abstraction†so unabashedly articulated. Suddenly my team of crack assault engineers storming into the Tractor Works under cover of smoke and HMG fire didn’t seem like such an achievement—the “factory†was only a piddling little cluster of hexes. I played SL and the rest of the series happily for many years afterwards, but that discrepancy always nagged at me. Maybe, I thought, I could get 8 or 10 more city boards and 200 tank counters and make it right?

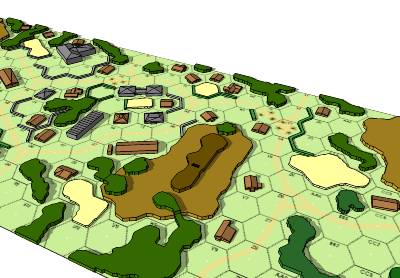

Of course Red Barricades, the first module in the historical ASL (HASL) series proceeded to do exactly that not too many years later. Historical ASL—even the name is telling—exposes some interesting tensions in the game system. Most ASL scenarios are played on generic or so-called geomorphic map boards, whose layouts depict a “typical†village, forest, piece of a city, etc. Despite the fact that the historical basis of the geomorphic scenarios was usually carefully established, the geomorphic map boards themselves—literally the foundation of play—were always a conspicuous abstraction. HASL was, in effect, the game system’s clearest acknowledgement of this phenomenon, substituting depictions of actual terrain (the Red Barricades maps were derived from aerial reconnaissance photographs taken by the Luftwaffle).

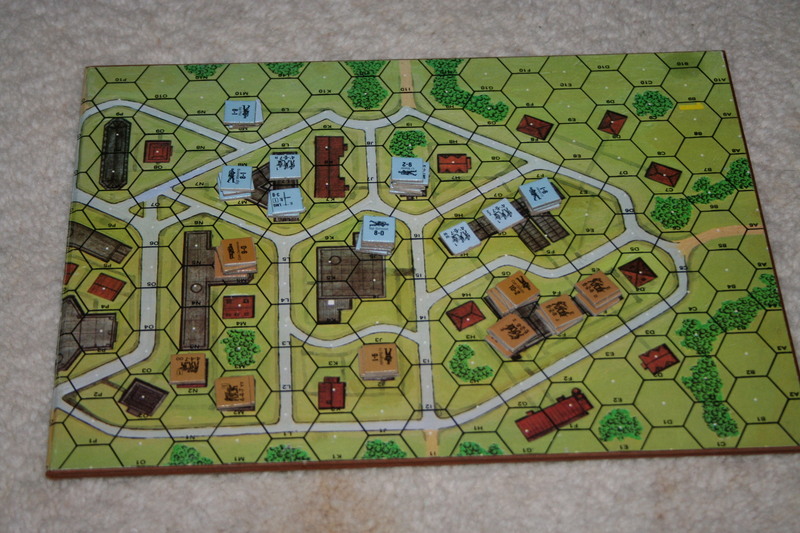

Urban terrain depicted with an ASL geomorphic board (left), Red Barricades (center), and actual aerial photograph of Stalingrad during the fighting.

One of the more brutal and bitter fights that occurred during the combat in Stalingrad in late 1942 concerned a Soviet stronghold that had come to be known as “the commissar’s house.†The ASL system features two scenarios that recreate this particular action, one using the geomorphic boards and one played on the Red Barricades map. Both are ultimately abstractions—the “historical†map includes stone walls whose 60-degree angles follow the outlines of the hex-grid, for example. But some interesting observations can still follow. In particular, I’m interested in whether wargame scenario design can be fruitfully mated with an area of analytical philosophy known as possible worlds theory. Possible worlds theory has in turn spawned applications in domains like narratology. Surely it is relevant to the design of interactive simulations, electronic or otherwise. In particular, I’m interested in thinking about possible worlds theory in relation to immersion or suspension of disbelief. When we play a geomorphic ASL scenario called “Counterstroke at Stonne,†we know that board 3 isn’t meant to be the small French village of Stonne, not exactly . . . but it could have been, and at a certain point we’re willing to suspend disbelief. Using a desert board, by contrast, would certainly be enough to break the illusion as would a major geographical feature like a river. But what about the chateau that’s depicted on one of the geomorphic boards used in the scenario, which, the story goes, is there because the designer read about a “chateau d’ eauâ€â€”a water tower. Whoops. A glitch, but one that has no real impact on the integrity of the scenario—after all, there could have been a chateau just outside the rural French village of Stonne, right? Had the false chateau appeared in a treatment of the battle based on actually terrain (like Red Barricades did for Stalingrad) it would have been regarded as a far more serious matter. But given that all such maps are still ultimately abstractions, how then can we account for the difference? Can possible worlds theory help here?

Jesper Juul, in Half-Real (MIT 2005) writes about rules: “Game rules are designed to be easy to learn, to work without requiring any ingenuity from the players, but they also provide challenges that require ingenuity to overcome” (55). He continues:

Rules are designed to be above discussion in the sense that a specific rule should be sufficiently clear so that players can agree about how to use it. Rules describe what players can and cannot do, and what should happen in response to player actions. Rules should be implementable without any ingenuity. (55-6)

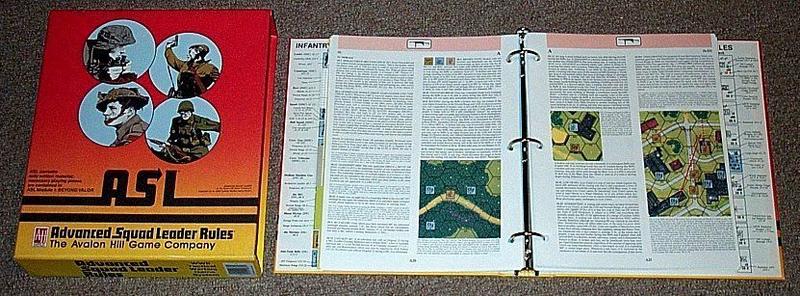

According to Juul, “Easy to learn but difficult to master” is the paradox at the heart of good game rules. But games with procedurally complex rules are not necessarily flawed or bad games. Advanced Squad Leader (ASL), originally published by the Avalon Hill Game Company, is undoubtedly the most procedurally complex wargame ever designed, and quite likely by extension the most procedurally complex boardgame ever designed. It is not easy to learn, nor master. The game (more properly, game system, you acquire it as a series of modules) focuses on Word War II small unit combat, with counters representing infantry squads and individual leaders, vehicles, and heavy weapons. Here is not the place to go into detail about ASL itself, which in theory allows a player to recreate any small unit action from any theater or phase of the war (see the Wikipedia entry linked above). What I want to focus on is the role of player error in the play of the game. Given the size, scope, and complexity of ASL’s rules—its procedures and their interactions—human error in the application of the rules is inevitable. This situation is anticipated in the rules manual itself (some 200 pages long), with the second rules case of the game stating the following:

A.2 ERRORS: All results stand once play has progressed past the point of commission. In other words, if an error is discovered after play has passed that point, the game cannot be backed up to correct the error, even if such an error is in violation of a rule. For example, assume an attack is resolved without application of a proper DRM [dice roll modifier], and a subsequent attack is resolved, or another unit moved, or play proceeds to another phase before a player remembers he was entitled to a DRM in the previous attack, thus changing the result. His failure to apply that DRM at the time of commission has cost him his right to claim that DRM. Or perhaps a player moves a unit before remembering that he wanted other units to attempt rally in the RPh or fire or entrench in the PFPh. Once the phase for execution of a particular action has passed, the player has lost any claim to that capability.

Thus the game builds the provision for error into its own formal system, so that error is accommodated within the formal structure of game play. The issue with ASL is not that the rules are badly written—the rules manual (pictured below) is for the most part a model of technical clarity—but that the number of rules, and their interactions and permutations is so vast that it is unreasonable to think human players, even experts, will always implement all of them correctly. (Early examples of play published in Avalon Hill’s own house magazine, The General, contained flagrant errors.) On the one hand then, a game of ASL’s formal scope and complexity represents a kind of limit case for Juul’s discussion of rules. (The number of interactions is so complex that ASL players has evolved an axion, COWTRA, “concentrate on what the rules allow.”) Yet ASL also provokes other kinds of questions, including what kind of pleasure one gains from playing such a procedure-heavy game.

An ASL game scenario is a kind of world building. In Juul’s terms, it is both incomplete and (occasionally) incoherent. The game system is capable not only of accommodating movement and firing, but a vast array of other actions. A building struck by an artillery shell may “rubble,” in turn collapsing other buildings around it. Underbrush may be set on fire. Squads may generate heroes, who can become wounded, but nonetheless survive to scrounge an abandoned machine gun which might then malfunction only to be repaired and then lost when the wounded hero is captured (he may then escape). A tank can throw a tread as it crashes through a wall, rotating its turret to fire at a target glimpsed for a moment through a narrow village street. These extraordinary permutations of rules interactions generate what players routinely refer to as “narrative.” (ASL is often described by its fans as representing not real world small unit combat, but World War II as it was refought in Hollywood film.)

Here is some of what ASL has to teach us about complex game rules:

I will be writing more about ASL in future posts, including its capacity for “narrative” and possible worlds theory.