Living Rules

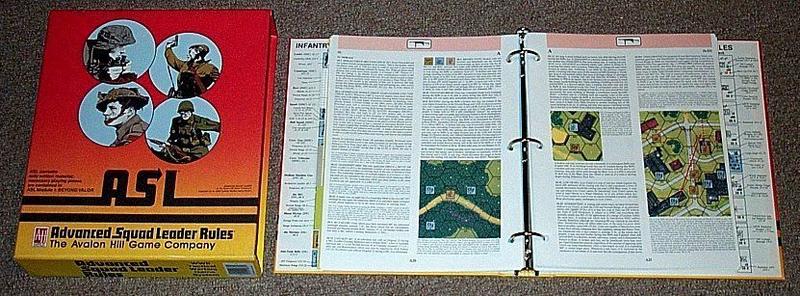

Remember the scene in The Matrix where they’re slotting cartridges into Neo’s head and he sits up and says “I know Kung Fu”? That’s every wargamer’s dream, except they’d want to sit up and say “I know ASL.” You get a new game, you pull off the shrinkwrapping, you unfold the map and fondle the components, but then there are the rules, oh man, the rules. Wargamers spend a lot of time with rules. Rule books often run 32 or 48 pages; anything 16 pages or less is considered “short.” Not surprisingly, wargamers have a different relationship to rules than most gamers. Reading rules it not “fun,” not exactly, but it’s part of the hobby and not without intrinsic interest and even art.

Games often have learning scenarios or programmed instruction sequences so players can gradually absorb a complex rules set, playing the game and layering on a new rules section every time. Some gamers set up a game and learn by pushing the pieces around, others like to give the rules a complete read through first. (There’s an ethnographic gold mine here for anyone interested in procedural learning.) Many games borrow and re-use similar concepts, and part of the interest of the hobby is viewing the rules as a window onto how designers are thinking about their subject and where they’re choosing to innovate. Yet many rule sets are ambiguous, poorly written, or otherwise open to interpretation and variants. Given their scope and complexity, wargame rules almost invariably have errata. In the old days, you would get the errata by sending a SASE to the publisher or maybe through one of the hobby’s house organs or zines if you had a subscription or were lucky enough to catch the right issue. Nowadays, of course, errata is available over the internet, and this distribution platform has changed the way rules are developed. Game companies have evolved the practice of “living rules,” where the ability to use the Web to electronically distribute rules means that a rules set is not necessarily fixed and inviolate once a game is published. Some gamers consider this a mixed blessing, partly because the rules can change under your feet, but also because the availability of living rules can sometimes become a crutch for shoddy playtesting.

Living rules turns out to be any interesting bit of phrasing, given the conventional wisdom that game rules are absolute and inviolate. Certainly this holds true for traditional games like Chess or Scrabble, but even contemporary Euro games tend to have very stable rules sets. One notable exception concerns the scoring of farmers in the popular tile laying game Carcassone, but even there you have variants rather than a living, evolving rules set. Wargames, by contrast, offer a game genre where rules sets are often malleable, based on player feedback, the deisnger’s changing intentions, new historical research, or all of these. Rules are therefore social texts, at least sometimes determined by the experience of a player community. (I would hasten to distinguish this from games played as part of folk traditions, where rules and variants are passed down orally.)

In the comments below, E Holmes says:

games are not static objects but are living, evolving structures that begin and end with human experience and involvement

With this I agree absolutely, but I have to depart from him on the next point:

Games are a human experience and reflect human experience; they do not operate on formal laws existing in any external ‘reality’.

In fact I think what’s unique about games is precisely that they operate on formal laws that arbitrarily impinge on our own reality. This of course is the well known concept of the “magic circle,” after Huizinga. Wargming underscores the extent to which the magic circle is a social construct, the product of a particular community of experts and enthusiasts. But to deny the formal ontology of games seems to me to deny the possibility of game play itself as anything other the unstructured make-believe play of a child. Or Calvinball. Agreeing that games (and their rules) are living, evolving artifacts seems to me to restore a useful social and material dimension to game studies, but it does not follow that we have to deny the formal ontology of game play.