Playing A Game of War

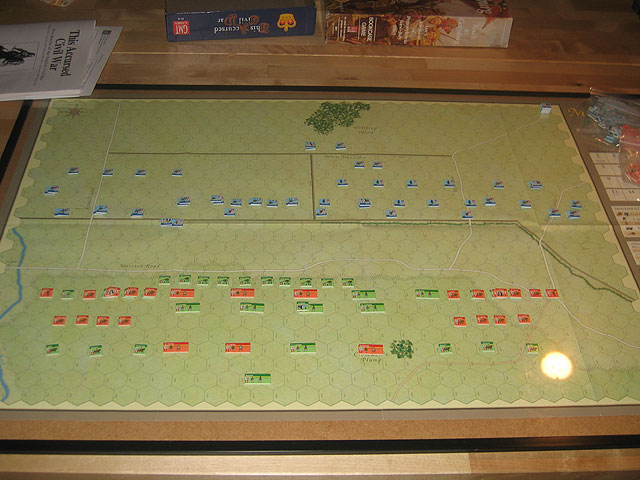

This past weekend I sat down with gaming bud Peter Bogdasarian to play through Guy Debord’s A Game of War (I own the Atlas Press edition). Peter (a successfully published game designer himself) offered some great insights, posted here with his permission:

Debord described his game as being based on Clausewitzian principles, a study in 19th century warfare and the importance of lines of communication. The scenario is a clash between symmetrical forces of infantry, cavalry and artillery. Debord’s game is therefore in the tradition of Tactics II and (going back farther) some of the military chess variants, such as the one designed by A.S. Yurgelevich in 1933. I think this balance of military power is where Debord (and similar wargames) depart from Clausewitz.

The key aphorism from On War is war represents the continuation of politics by other means. Debord’s offering, however, divorces the conflict from its political aspect. These two nations are equally powerful and, on paper, possess no intrinsic advantage over one another. Furthermore, they can only triumph by either the complete destruction of the other’s army or the seizure of his two arsenals (which requires conquering one’s way to the back of the map).

Consider the situation – two equivalent nations of equal might have decided to wage a war to the death. Wars are avoided under these conditions and, when they must be fought, are not begun with the idea of fighting to the finish.

Conflict normally results from the perception of weakness, either in the present or forthcoming in the future. Germany, in 1914, sees Russia rearming and Russian officers enthuse to their Prussian counterparts about how they will crush them once the projected modernization is complete. The foes of the French Revolution see a threat to the infrastructure of their own countries from revolutionary ideals – then, as the Allied armies meet with defeat after defeat, Napoleon sees the potential to turn battlefield victories into Empire. By failing to make credible the calculus behind its struggle, Debord’s game fails to grasp the essential, enticing element of Clausewitz’s narrative of war.

What players are left with is an engagement between equal antagonists where the defender enjoys the advantage.(*) Units in A Game of War are stronger on the defense than on the attack and the limited number of moves allows a defender to bring more force to bear where counterattacking. The only recipe for success under these conditions is for a player to overstack a wing of his army (as I did against Matthew in our game) to attempt to attain decisive local superiority. The historical answer to such a strategy is for the defenders to cede territory for time, seeking to draw the invaders forward and strain their lines of communication.

But Debord’s game gives players no incentive to fall into this historical pattern. I possessed no reason to push my forces forward after seizing what I could from the initial encounter battle. Taking territory from Matthew brought me no closer to victory and did not weaken his forces through desertion or despair. My army cost me nothing to sustain as a force in being – I could maintain it for the length of the game in place without any cost to my society. The clash between equal antagonists (as one might expect), is therefore likely to lead to stalemate (Columbia’s Wizard Kings often ended this way).

What’s missing is an underlying narrative to drive the action. Imagine a different scenario – one where Matthew starts with an army enrolling, say, half the infantry of mine, but with two scheduled drafts of conscripts which will ultimately make his force half again as large. Now, when we sit down at the table, my incentives are obvious – I must attack while I enjoy superiority in force and, if need be, risk my whole army to do so.

As I played A Game of War, I found myself considering these other, more fertile variations. What if my country enjoyed the advantages of the Chassepot rifle or Krupp gun? What if I chose to deploy a small corps of hardened professionals against seemingly endless waves of peasant conscripts? These are scenarios which both fire the imagination and evoke the stories of 19th century war; not this dry confrontation of symmetrical powers fielding identical military systems.

Creating a game about war thus requires more then selecting military units and engineering a system – it is about framing the narrative of the conflict between the players. War, even in the abstract, cannot be removed from political realities. To depart from this model is not only to lose the essential element of war, but also an essential element of the game itself by removing players’ incentives to take action.

(*) – assigning the advantage to the attacker (as Chess does with its system of captures) can create a different dynamic – players are driven to aggression against the other side because the defense is made untenable. Stalemate can still result in the endgame as capability wanes from the destruction of a player’s more capable units.